Sparring about your Lean issue?

Call René

Somehow it is surprising that business schools teach very little about management, and if they do, all the learning is classroom-based. Instead, they should go to gemba.

Temperatures seem to be rising worldwide, but in Boston it's still cold in the winter, and I'm getting old. So a few years ago I thought a little about the cold/old problem and decided to do something bold: Become a short-term professor in business schools in warm places in emerging economies during the winter in Boston. It's been fun and I've learned a lot (and I hope the students have, too). Going to the gemba in the huge MBA industry, which began in America in the 1880s and is still spreading around the world, has given me a chance to get to the bottom of the situation, get to the bottom of the problems and even experiment with some countermeasures.

Perhaps the most amazing finding, when first encountering gemba, is that business schools do not actually teach management. Instead, they teach functional skills, usually tool-based: strategy, financial analysis, accounting, marketing, purchasing, etc.

Even in operations management courses, the little slice of the B-school world I get to participate in, operations math is actually taught: queue theory, economic order analysis, bottleneck analysis, variation reduction (using tools from W. Edwards Deming's kit on the road to six sigma). And note that "operations" are limited to transactional activities - manufacturing in the factory, claims settlement in an insurance company, the flow of patients through an emergency department in a hospital. In the real world, every value-creating activity in any organization is an "operation," and every activity must be managed for stability and improvement.

General management is sometimes discussed casually in business policy courses, where students can learn about the organizational chart as a conduit for authority and the tools of modern management: setting goals through key performance indicators (KPIs) as part of a top-down annual plan and budget, holding direct reports to their KPI promises, handing out rewards for good performance and punishments for bad, and delegating problems and improvement activities to staff experts. But these points are quickly covered in a few lectures without opportunities for students to actually practice management. The assumption in the B-School world seems to be that graduates will find jobs in organizations with complex, pre-existing "management systems" and that students must quickly adapt to practices in their new environment. Training them in a different, rigorous way of managing might even be a disservice that jeopardizes their career development!

The little that business schools teach about management, they teach in classrooms: theory via PowerPoint and practice via case analysis, the innovation of the Harvard Business School at the turn of the century.

"Their idea of going to the gemba is a quick 'study tour' to see tools in action, followed by a discussion back in the classroom."

The dynamics of case teaching are particularly interesting. The student has written down all available information from the case - no deeper investigation on the gemba is possible to verify that the data is what Taiichi Ohno wanted: facts. Accurate, timely and relevant. (For me, getting the facts to clarify the problem is the most difficult and rewarding part of management - the left side of the A3).

So the goal for the student is to quickly define the problem and quickly find the solution, using the data and tools taught in the course, and to appear as confident as possible in developing a PowerPoint presentation to share the conclusions. Is it any wonder that the world is awash in B-school-trained managers - the ones who give Lean practitioners a headache every day - working in conference rooms far from the gemba to quickly define the problem and prescribe the solution, while demonstrating an absurd level of self-confidence? (See Professor Henry Mintzberg's recent blog article on how this plays out in practice as B-School students rise to CEOs and perform worse than CEOs who have never been anywhere near a management school - MBAs as CEOs). Some disturbing evidence).

Here's a thought experiment: Let's assume B-schools don't really think their practices are effective or the best way to create good managers. So what can they do?

The place to start is to ask what "management" actually is. In our Lean world, we believe it is (1) reaching agreement on what is important for the organization to achieve (through hoshin planning involving every employee at every level), (2) taking initiatives to counteract important problems or to develop important initiatives (through A3 analysis by line managers), and (3) creating and maintaining basic stability in every "operation" (through day-to-day management). And, most importantly, we must agree that management is not a theory, but a social practice that can only be mastered through repeated cycles of daily management, A3 analysis and hoshin planning with the help of a teacher (or coach or sensei, if you will) who deals with first-line value creators and lower-level managers.

This suggests that the heart of any management education should be on gemba, with direct involvement of the people doing the actual value-creating work. So instead of analyzing problems and jumping quickly to solutions without gemba knowledge, B-Schools should find gemba for each student on an ongoing basis and take each student through extended cycles of hoshin, A3, and day-to-day management. The students would win, the host organizations would win, and - I predict - professors would also become a more satisfying profession.

To do this, B-Schools should develop long-term relationships with those organizations that provide gemba experience and, in effect, become their centers of management training. This seems like a steep hill to climb, but I don't think it's crazy. Modern management - with its functional tools - was spread around the world by B-Schools after World War II and continues today in new B-Schools being established in the emerging economies where I teach. What is needed now is the courage to experiment on a different path. Anyone have an A3 analysis for B-Schools?

(Full disclosure: Professor Peter Ward of the Fisher College of Business at Ohio State has been a board member of the Lean Enterprise Institute for many years, which has given me the opportunity to discuss these issues and observe the Fisher School's interesting experiments in this direction. For details on a gemba-focused MBA program in Operational Excellence click here).

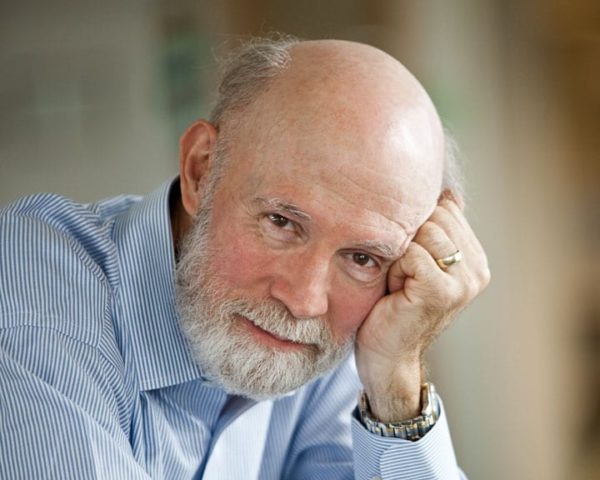

Management expert James P. Womack is the founder and senior advisor of the Lean Enterprise Institute. The intellectual basis for the Cambridge, MA-based institute is described in a series of books and articles co-authored by Jim himself and Daniel Jones over the past 25 years. Between 1975 and 1991, he was a full-time research scientist at MIT leading a series of comparative studies of global manufacturing practices. As research director of MIT's International Motor Vehicle Program, Jim led the research team that coined the term "lean manufacturing" to describe Toyota's business system. He was president and CEO of LEI from 1997 to 2010, when he was succeeded by John Shook.

Sign up for our newsletter